The old chair bodgers of Buckinghamshire are now relegated to history, the last few of them doggedly clinging on to their traditional way of life until the late 1950s. I have been privileged to know some of these craftsmen from the Beech-clad Chiltern Hills and have spent many a cosy hour by their firesides and in their disused workshops sharing their old tales and dry sense of humour. They are all gone now but their legacy is every where. You are supported by their craftsmanship every time you sit in an old Windsor chair. Every leg, spindle and stretcher contains the spirit of these men, the essence of the Beechwoods is still there and if those turnings could talk they would speak of spring Bluebells, red Squirrels and autumn winds.

Much has been written of these pole lathe turners and the contribution the chair bodgers made to the furniture-manufacturing town of High Wycombe, and, as is the way with history, distortion and myth tend to creep into the story. I have seen references to chair bodgers as being ‘itinerant’ but they never were. They were family men with a cottage to go home to every night. There was a garden to tend and animals to feed. Indeed, a number actually worked at home in a bottom of the garden shack or a cottage lean-to preferring to have their timber delivered rather than work in the woods.

For the chair bodgers of Speen, Lacy Green and Great Hampden villages the buying of timber was a great annual social event. The Hampden estate of the Duke of Buckingham owned most of the local Beechwoods and sold ‘stands’ or parcels of standing timber every autumn. A catalogue was issued to all prospective purchasers detailing the number of trees and species in each lot, its location and accessibility.

Armed with a catalogue the local Bodgers spent a day visiting each location and weighing up the pros and cons of each lot, were there enough trees to keep them busy for the next twelve months? was it easy to get a wagon on to the area? how far from home (walking distance) was it? They would check how sheltered or exposed the situation was but most of all they would study the trees. Were they straight from being sheltered or ‘rimey’ from exposure on the hilltops? Would the trees be ‘good or bad splitters’ or contain a devious grain that meant extra conversion time and more waste. What if your favourite lot proved too popular and you lost the bidding, it was all these considerations and uncertainties that made the auction such a big day in the chair bodger’s calendar.

The auction was held in a pub, the Hampden Arms, Great Hampden with the bidding starting at 1pm. The venue was open from 10am and the beer was free, paid for by the Hampden estate. This may be seen as an act of generosity by the woodland owners but was more of a ploy to loosen pockets and create over enthusiastic bidding later in the day. Successful buyers were given six months to pay. One bodger explained how useful this arrangement could be should that particular years work not go according to plan. If a bodger got into financial difficulties he could sell the remainder of his trees and with what he had made previously could at least hope to break even when the time came to pay.

An essential concession by the vendor was the 12 months allowed for clearing the woodland of purchased trees and the erecting of a shelter for the lathe. In wintertime the chair bodgers started out for work on foot or bicycle, usually a journey of several miles and arrived at the woodland edge before daylight. These men knew the Beechwoods better than any one and yet on foggy mornings were glad to follow the trail of shavings they had left the night before. Candles were the main light source after dark; one perched on top of each poppet (head and tailstock). It was an eerie thing to see the glow of flickering light through the evening mist and hear the ‘razzle’ of a gouge against revolving green Beech!

Owen Dean lived only a stones throw from the Hampden Arms and was a regular bidder at the auction. He worked in partnership with his brother Alexander and they attracted a lot of attention in their latter years due to their being two of the last chair leg turners remaining. Even the BBC made a film of them in 1950. In earlier times the traditional Bodgers shelter or ‘Hovel’ was an ‘A’ framed arrangement, usually thatched with straw and twigs. Latter the thatch was sometimes replaced with corrugated iron. From the 1930s the Dean brothers used a panelled shed in the woods so they could lock up their equipment more securely, formally tools could be left in the safe knowledge that they would be there next morning, Owen’s lathe can be seen at the High Wycombe Chair Museum.

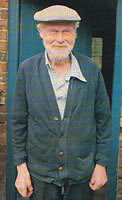

Another regular at the Hampden estate auctions was Reg Tilbury. He lived in the same row of cottages all his life and Beech trees planted by Reg as a boy, even today stop just short of Reg’s old front room window with only a lane intervening, he was a true man of the woods. Born in 1898 he decided at the age of 13 to work in the woods as a chair bodger. He once told me:

It was hard work for little pay, I worked from 7am to 6pm and brought home 1/6d (71/2p) a week. I knew others who started work at 6am.

Jack Rickson took Reg on as an apprentice. Reg told me:

I used to do all the sawing on the (saw) horse, that was all I did for a long time. The chance to turn legs came when I was about 15. Jack used to say I ought to pay him for teaching me!

Reg joined the army in WW1 and each week sent his mother sixpence (21/2p) from his army pay packet. She saved all the money and presented it to him. Reg used the money to start up in business on his own, it gave him the capital to buy timber.

Reg used a pole lathe up to 1924 and then invested in an oil engine that he set up in a wooden outbuilding, this drove a wooden bedded power lathe. Two men were employed to convert green logs into chair legs in the cottage yard using traditional methods to split timber, shaping with the side axe and to shave billets on the shave horse. The new belt driven lathe was the only concession to modernity. The new engine also provided power to a circular saw that proved an enormous help in the other half of Reg’s business, firewood. When I first photographed the old workshop in 1982 it was a ruin but still housed the Petter oil engine and remnants of busy woodturning days. Reg had given up the life of a chair bodger to grow strawberries but still revelled in telling stories of the days when things were altogether different.